Storytelling Skill

“I KEEP six honest serving-men (They taught me all I knew);

Their names are What and Why and When and How and Where and Who.”

Rudyard Kipling, an English journalist, short-story writer, poet, and novelist

Until a decade ago if a suit-wearing manager had announced at a board meeting that he wanted to tell a story to convey a message, instead of using a PowerPoint presentation full of graphs, they probably would not have taken him seriously. Maybe he would have dared to spice up his presentation with some story along the way. But surely, they would not have called it “storytelling.”

Today, it is clear to everyone that storytelling is an ability we should all have in our toolbox, not just as a buzzword, but at a level that can be utilized. Everyone agrees that stories have great power to comfort, connect, create change, share a vision, inspire, and, most powerfully, to heal. Nowadays, everyone is engaged in storytelling, even if it’s really an anecdote.

We design visual storytelling.

But for the sake of clarity, let’s start with a definition.

Merriam-Webster defines “story” as a series of incidents or events conveyed in an imaginary or truthful narrative. EM Forster explains the difference between relaying facts and telling a story: “The king died and then the queen died” is a series of facts, but “the king died and then the queen died of grief” – that’s a story. Robert McKee, whose book Story is the bible of anyone who writes, says that a “story is a series of acts that build to a story climax which brings about absolute and irreversible change.” (he even twitted it)

One of the essential aspects of a story, and which few talk about, is a concept I came across in Robert McKee’s book. It’s called “aesthetic emotion” and it has an interesting connection to design.

McKee references Aristotle’s search for meaning in the philosopher’s question: How is it that when we see a corpse in the street we have a particular reaction, but when we see a theater performance we have a different one? The answer, as strange as it seems, is as follows: If you were to come across a dead body in the street, you’d exclaim, “Oh my God, he’s dead!”, run home and only afterward think about the significance of that death. Only after a bit of time has passed would you begin to ponder our human mortality, and the like. However, if you were to see a play that involved a death, such as in Hamlet, the idea would strike you immediately.

The reason for this is that “meaning and emotion exist separately in life. Opinions and passions move along different tracks, meet momentarily, and are generally in conflict…. Moments that spark both emotion and ideas are rare in life. They only come together in art.” That’s what a story is – the tool by which we can create a moment of “aesthetic emotion,” the simultaneous encounter of thought and feeling.

McKee explains that a well-told story provides us exactly that which we cannot get out of real life: an experience that is both meaningful and emotional at the very same moment. In life, experiences take on meaning only after some time has passed.

You may be asking: “How is this related to design?”

The “story” is one of the most significant tools in the world of design. Moreover, there have been quite a few lectures declaring that design is s (a book even came out on this theme). The explanation for this is precisely the reason provided by McKee: “aesthetic emotion.” Design is storytelling because it can connect an idea and an emotion in a single moment, which is the most powerful method of creating a memorable experience.

But there’s more. In a world where information is available at the click of a mouse, data loses its value. What becomes important is the ability to present the facts in a content-rich context and convey them in an exciting way. This is the essence of storytelling ability. A story helps us understand things when they are presented in a different context.

Design is narrative because we design expressions that become the language creating change. Many expressions that are typical of transitions often need to be represented in infographics, so that the terms can be internalized within organizations.

If we’re already discussing change and storytelling, it’s impossible to go on without mentioning The Hero with a Thousand Faces by Joseph Campbell – a cornerstone in the world of stories. Campbell argues that all stories are based on the same principle, called “the hero’s journey.” The journey has three main parts: departure, initiation, and return. During the departure stage, the protagonist is required to leave his home and world for a new and unfamiliar place. The initiation stage is when the protagonist is forced to handle difficulties and face trials. Along the way, mentors help him overcome these challenges. Through these confrontations, he is transformed into a new person, eventually reaching the third and final stage in which he returns home, back to the starting point, but as an improved and more self-aware version of himself.

This journey exists in every business story, as well. The company departs familiar ground in search of a new product or service, the Next Big Thing. It encounters difficulties along the way, enlists the help of experts, and finally creates something new that works.

Visual storytelling includes all of the elements mentioned so far, but also makes use of design, images or videos to engage viewers in an effort that will evoke emotions, communicate, and motivate viewers to take action. These additional tools strengthen the story and make it suitable for the digital age, for the image economy.

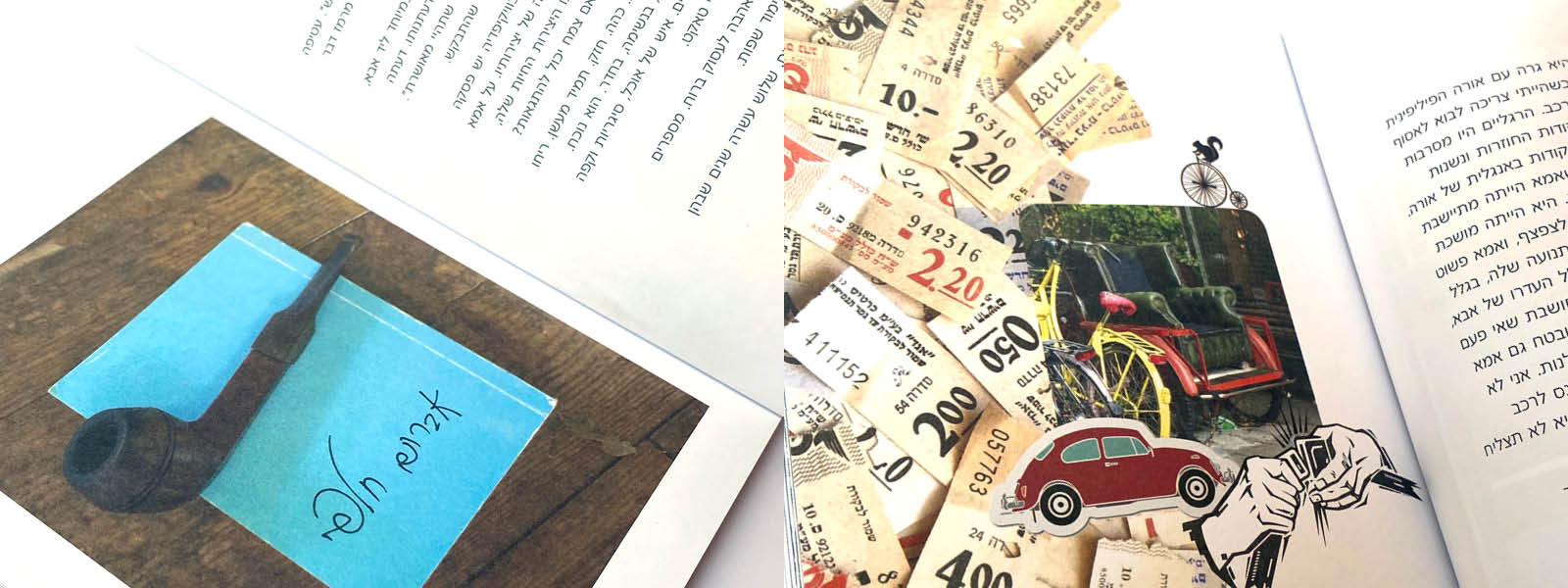

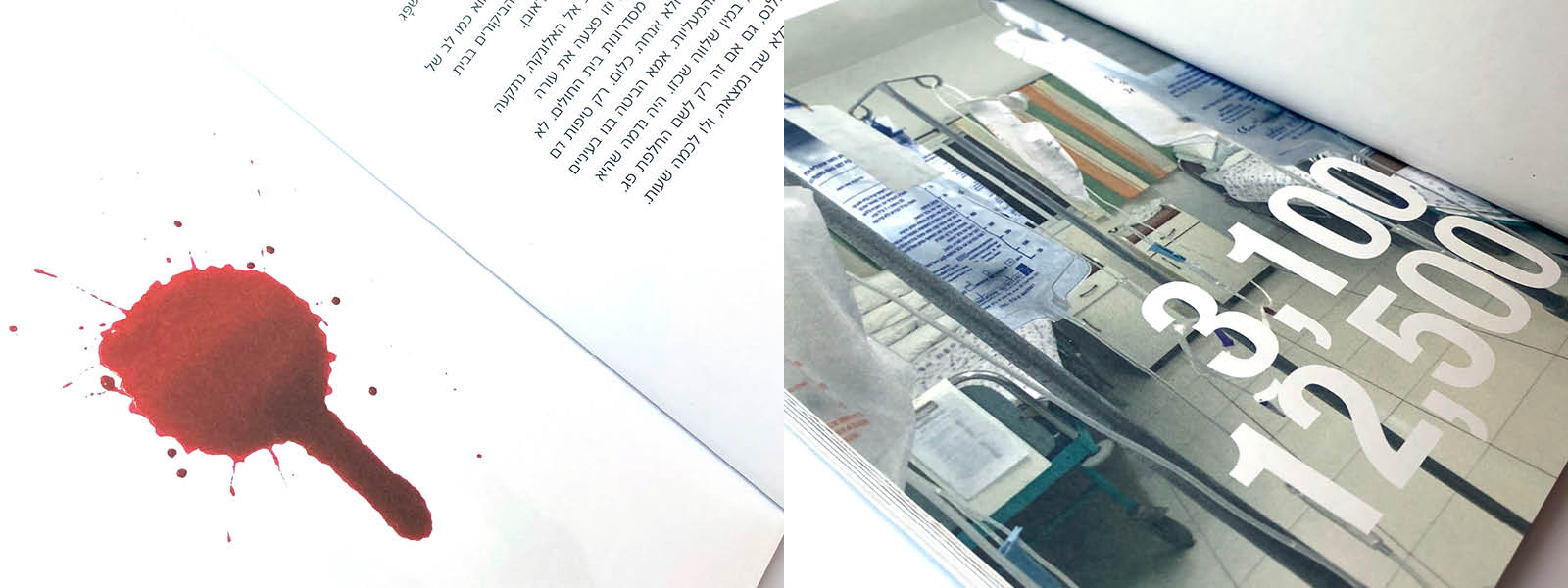

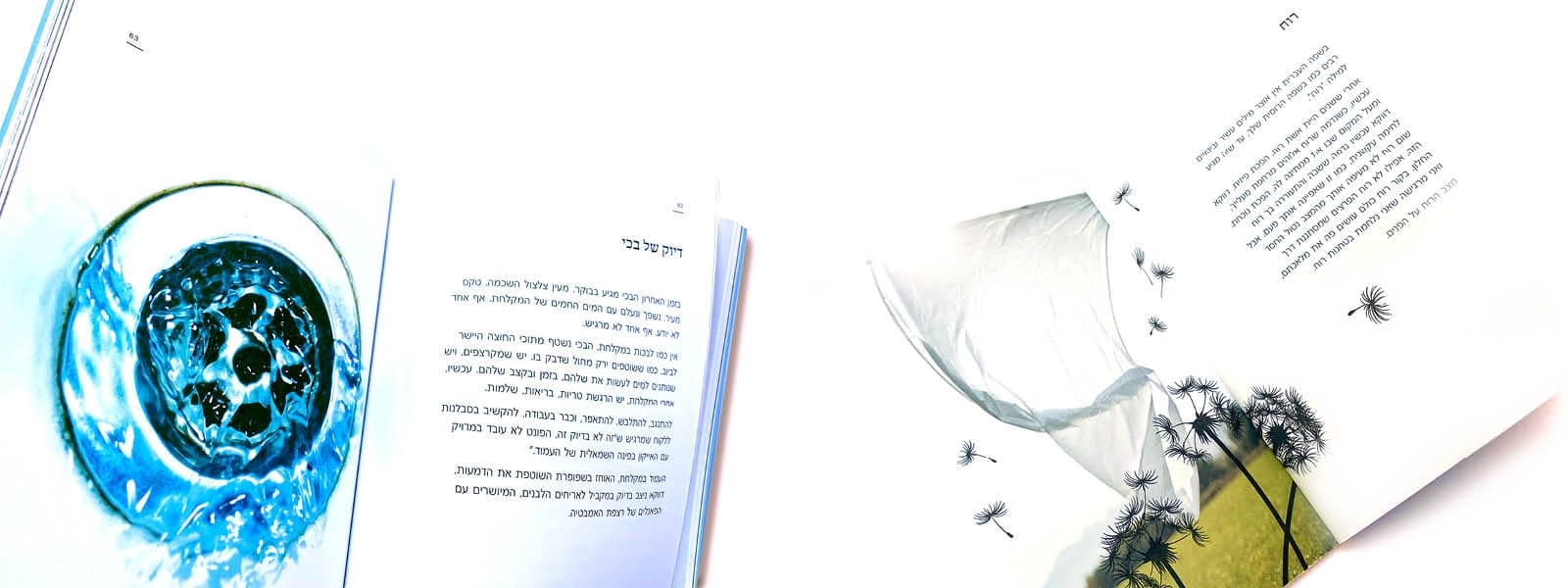

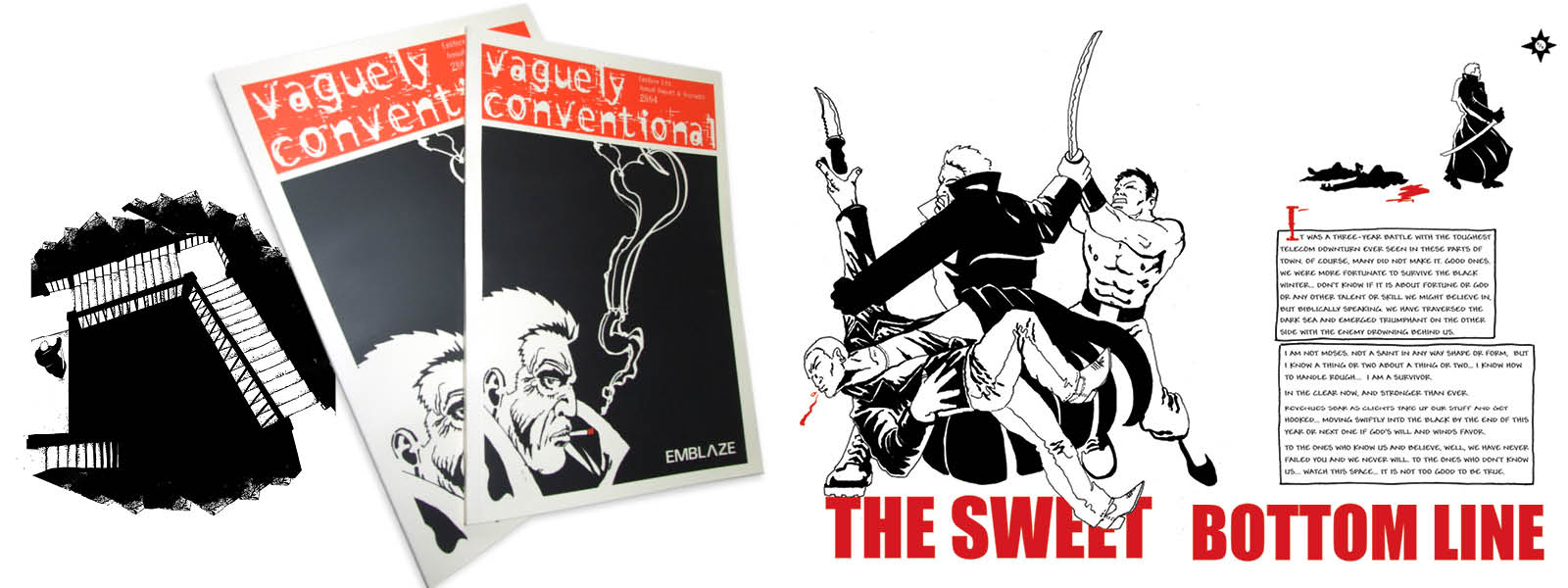

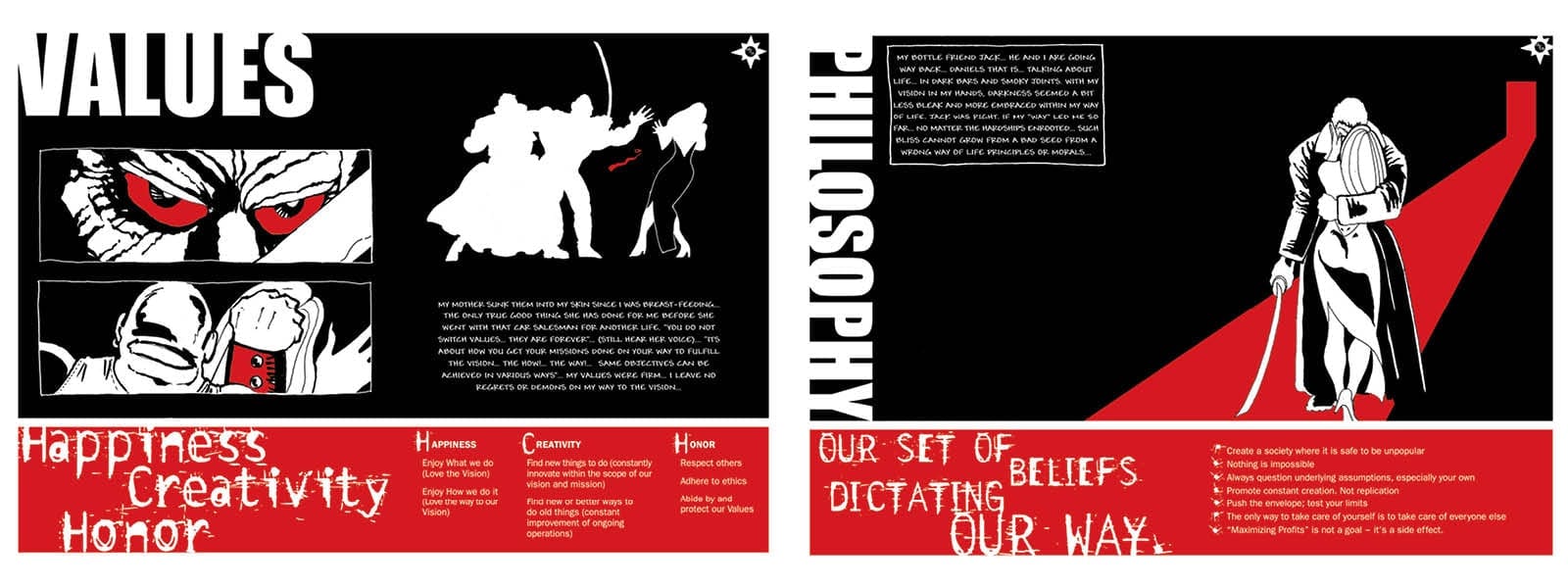

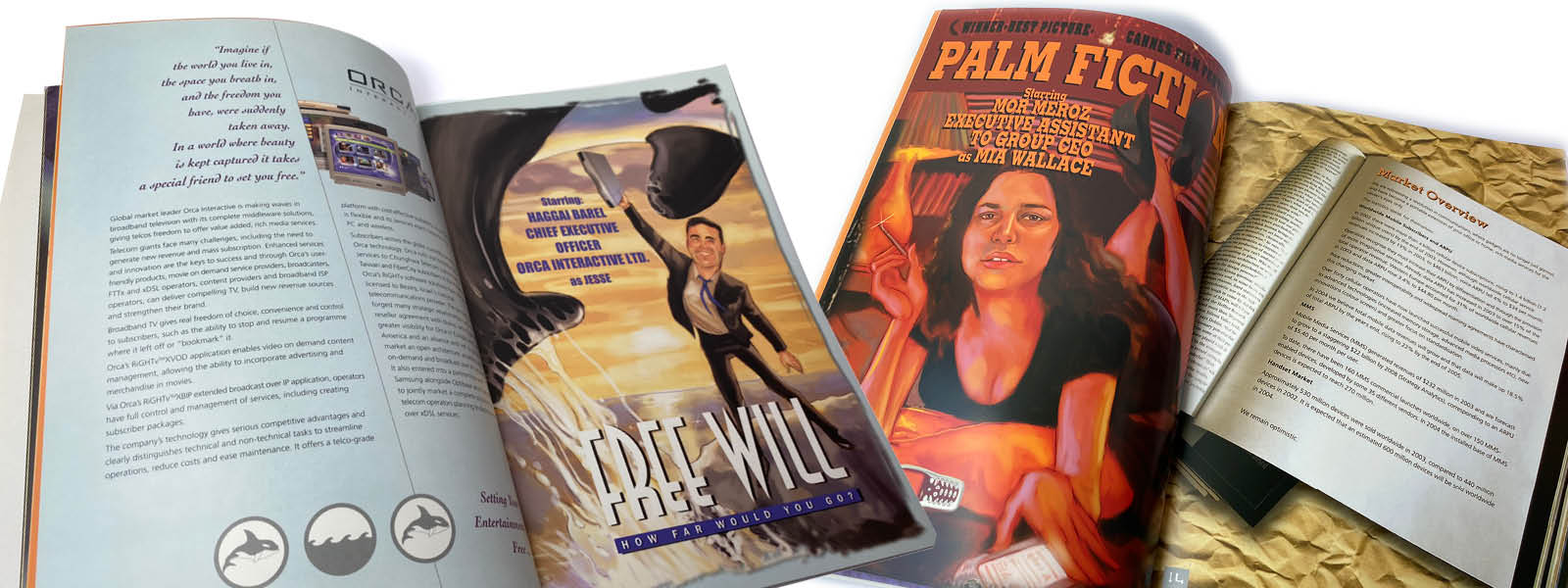

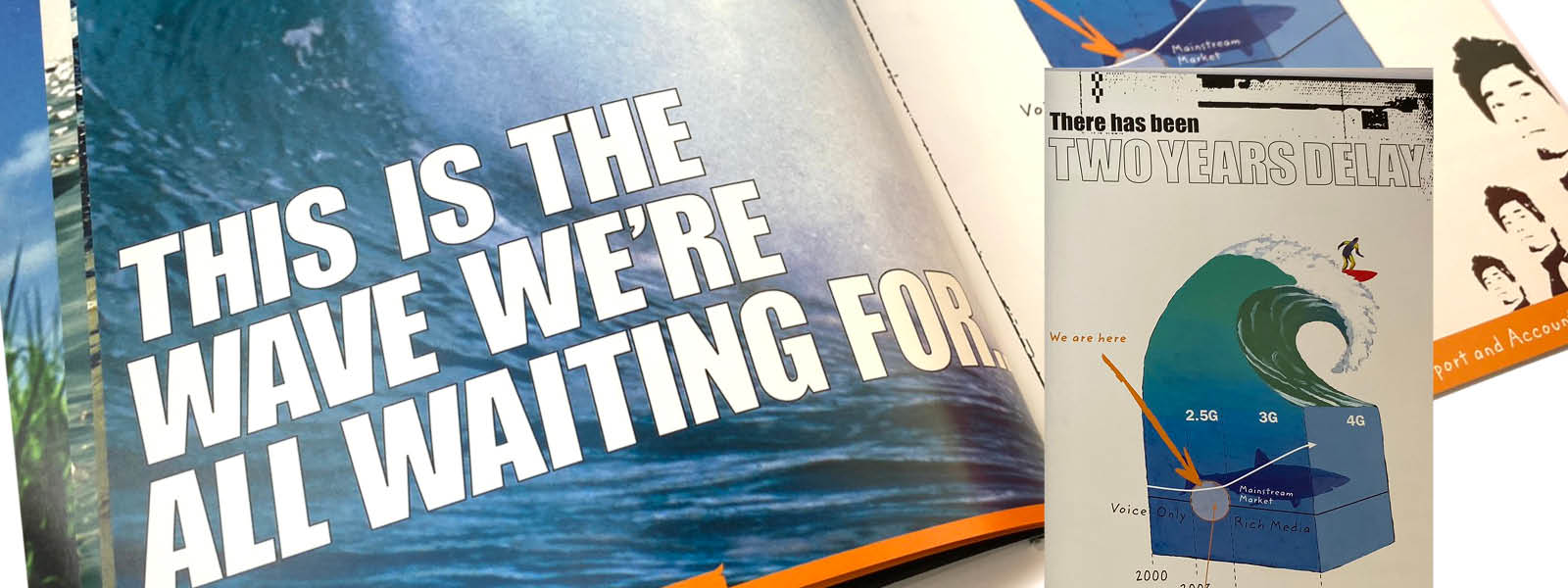

Most of our projects are stories. Visual stories. The series of examples we chose to present here are from Emblaze, a company which boldly believed in storytelling and did just that in its annual financial reports for several years. The brief we received was every designer’s dream: create something that analysts could not ignore.

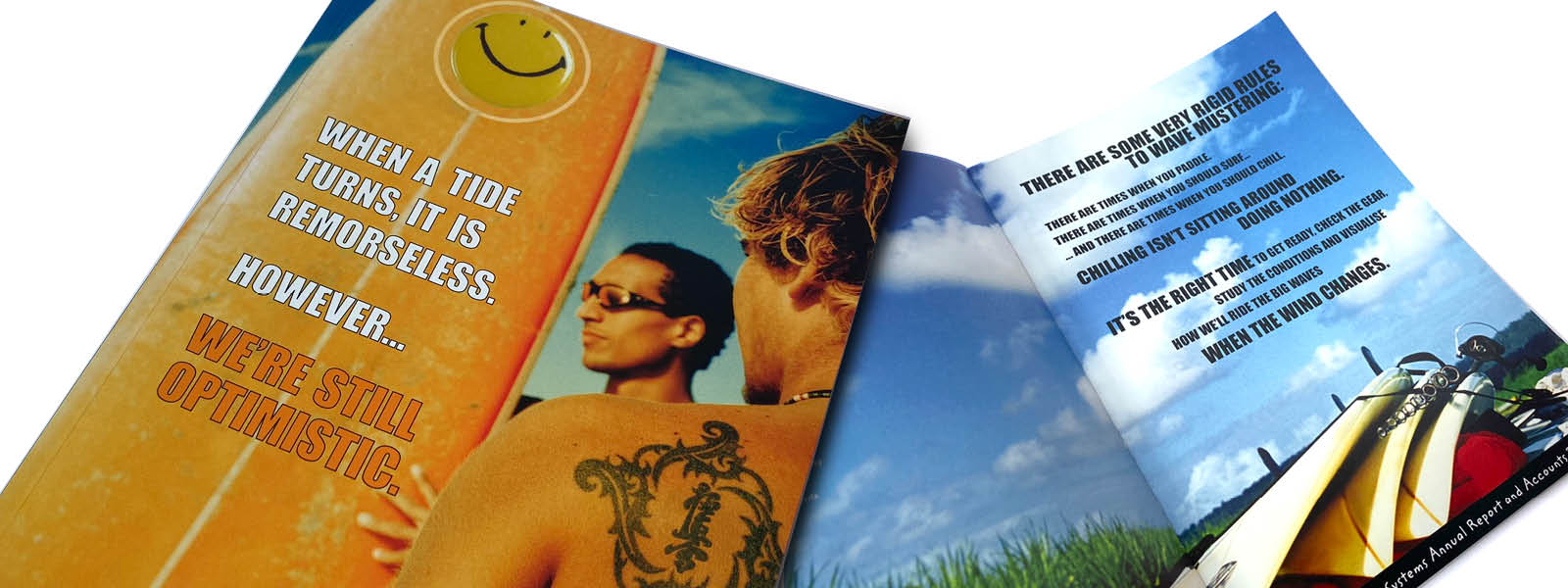

The result was an example of how a company’s vision, values and philosophy can be conveyed through a dramatic story illustrated in black, white, and red (illustrations by Terry Marx). A different year, we based our design on movies with clear analogies (illustrated by Uri Fink). And there was also “the year of the surfboards”: a story about the calm sea, a near-drowning, shock, and anticipating the big wave.

A different example of work is the book Two Coffees, Please, that I wrote, which managed to touch many people and convey the message that “life is now.” Not tomorrow, not later, and not in retirement.

Mina Portnov Mishan